Seeing as how our very beliefs are founded upon the fundamental premise that God exists, it seems paramount to ask: is it rational to believe in God? To be specific, I am asking whether or not it is rational to believe in the existence of a God. I’ve always found “Pascal’s Wager to be a fascinating prudential argument for believing in God’s existence. Within the last argument of three in Pensées, Pascal applies decision theory and the concept of infinity to come up with a wager.

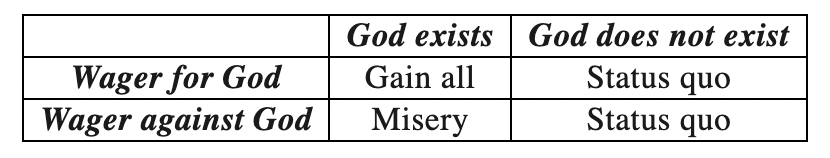

Suppose you make a bet on whether God exists or not, assuming infinite effects. On the one hand, if God exists and you have chosen to believe in him, then you will be granted eternal salvation. On the other, if God exists and you choose not to believe in him, then you will be granted eternal suffering. No big deal. The consequences seem simple enough. Now let’s examine the other possibility. If God doesn’t exist, and you choose to believe in him, you lose nothing. If God doesn’t exist, and you choose not to believe in him, you naturally lose nothing again.

While on the outset the argument seems simple enough, there are a numerous number of assumptions that are made, all of which I will accept as they seem to hold no bearing on whether or not Pascals argument is a good way to think about our belief in God. Here is the relevance of each of them to the Christian framework:

Assumption 1: The probability of God’s existence is 1/2.

- Essentially Pascal takes utility to be linear in terms of number of lives, and even when extending this linearity to infinite lives, each individual life has a 50% chance of getting God’s existence right. A wishy washy argument at best, but poses no problems.

Assumption 2: Wagering for God brings infinite reward if God exists.

- As Christians, we know this is absolutely true. Although we cannot conceive of it at the moment.

Assumption 3: You must wager.

- Pascal takes away agnosticism as an option here, but it seems this is certainly a correct assumption. It is quite rational to think that we must eventually make a choice within our hearts on whether or not God exists, and not making a choice seems just to be the equivalent of living without direction.

Assumption 4: The consequences are eternal, and we look at such consequences in terms of utility.

- Again, the Christian can accept this. Romans 6:23, note the word eternal.

Assumption 5: If God doesn’t exist, you lose and gain nothing from your decision.

- We accept this again because in a Godless world, I could kill a man and be killed, and none of it would make any difference because in a millennia maybe the atomic heat wave just reduces the universe to Cosmic Microwave Background radiation.

A decision matrix presents our options quite simply, and I think it is quite clear the only rational choice is to believe in God, if not only for a selfish perspective of utility. One would say that the potential outcome is infinitely better if we choose to believe and there is no God vs if we don’t and there is, since the worst outcome of wagering for God superdominates the best outcome of wagering against God. But is this what we mean by believing in God? This makes it seems like we are believing in God by making a logical calculation of outcomes, but in its very core, belief involves a degree of faith. Biblical faith is not just a mental assent for what one accepts to be fact, if that were the case, even demons “believe” in God in this way: James 2:19. To say that one must believe in God because it is the most rational thing based on a decision matrix calculation goes against the very doctrine of faith.

The Christian cites evidence like…. Consciousness is not explainable by science to the least degree and even the simplest reduction of a cell’s function cannot be fully understood, etc. ad infinitum. The atheist responds: Any sufficiently advanced form of technology seems like magic. Our science will eventually be able to explain all laws of nature and life.

Is evidence a good way to come to believe in God? To the Christian, God is evident in all forms of nature and causality by simple observation, but the atheist sees quite the opposite. It boils down to this: we can’t prove God. If we could, we’d be God.

The Question Revisited

The problem becomes very clear at this point: if we have no evidence to prove God’s existence, and if believing in God simply because it is the option that brings most personal utility to us is not actual belief, then is it rational to believe in God?

To answer this question, one approach we might take is to clarify what belief means here. Barring aside much too complicated discussion of free will and choice, my intuition to approach this problem is quite simple: split the time segments for when you ask whether or not it is rational:

T1: Before a person accepts God, believing in God is completely irrational.

T2: After a person accepts God, it looks to be the only rational thing to do.

T3: The moment when a person accepts God. I take this to be an instantaneous moment, and will ignore this to not complicate things.

After thinking about it with this new splitting of timeframes, it looks to me like what this shows is that my initial question is somewhat loaded. And no, not in that sense. Let’s get specific once more. I mean loaded in the philosophical sense: it presupposes a false assumption(that oftentimes the person disagrees with). The assumption behind the question “Is it rational to believe God” is that belief in God is a rational process at all. While in hindsight of experience, belief in God is the most rational thing to do, because I believe God exists, the atheist can never believe it is rational because he never believes God exists in the first place.

Naturally, two questions arise. If the only way for it to be rational to believe in God is for you to already have believed in him, doesn’t it seem like there is no way for the unbeliever to think that belief in God is rational. My response: you are correct, for simply the reason stated above. T1: Before a person accepts God, believing in God is completely irrational. This, I concur.. Now perhaps the harder one: If the only way for it to be rational to believe in God is for you to already have believed in him, do you believe in God first, or are you rational first? If the two are dependant, surely there must be a temporal order to the events? If we say that rationality comes first, that makes it seems like once more belief in God is a cold hard calculation based on a decision matrix like Pascals Wager. If we say that belief in God comes first, that implies we can freely choose to believe in God.

This doesn’t sound like too much of a leap right? Surely we can choose to believe in God? Right??? The Arminian says: “Sure! We can absolutely choose by our free selves to believe in God. While we are not free from sin, we are free from necessity through a temporary prevenient grace(think of it like free will while we’re alive). “The Calvinist is enraged, grimacing in anguish, and replies: “No, atonement is limited, and salvation is from God’s irresistible grace, where you then are able to believe in God. The very ability to believe in God comes from God.” The Lutheran shakes his head, and thinks aloud: “Anybody can get Salvation if he has Faith. If predestination is true and we cannot choose to believe in God ourselves, that would mean God predestines people to hell.”

This points to a crucial dilemma: How can salvation and life be only given by God, but we have the free will to choose sin and death? A variation of this dilemma appears for all three protestant denominations.

My answer to this dilemma? I think I will grapple with this next time. I think now that I have all this down for my a first blog, I can go to bed. It’s 4 a.m. after all. Stay tuned for the next blog!

I am glad see so excelent post!